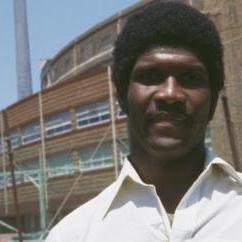

On March 10, 1974 Lawrence Rowe sculpted what was arguably the most elegant Test triple-hundred of all time. Abhishek Mukherjee looks back at an enchanting innings that combined grace, power, and efficiency at the same time.

West Indies were leading the series 1-0 when the teams arrived at Bridgetown for the third Test. Though England were outplayed at Port-of-Spain, they had fought back admirably at Kingston. Kingston was Lawrence Rowe’s hometown, and the prodigy — as he was being hailed in the world of cricket — made up for his failure at Port-of-Spain with a classy 120.

He finally ended up with 567 runs (over a quarter of his career tally of 2,047) at Sabina Park at an astounding 113.40. Till this point, he had never scored a First-Class century, let alone a Test century outside Jamaica. In his three innings at Bridgetown, Rowe had scored 0, 51, and 16. Would he be able to change the trend?

Julien’s wickets, and Greig and Knott’s fightback

After Rohan Kanhai won the toss and put England in, Bernard Julien, coming on as first-change, made early inroads after Garry Sobers removed the English captain Mike Denness. He removed John Jameson, Geoff Boycott, and Dennis Amiss in quick succession, and England were reduced to 68 for four. After a fightback of sorts, Sobers brought on Bernard Julien again, and he removed Keith Fletcher.

From 130 for five, Tony Greig and Alan Knott, both reputed for spirited batting, took the attack to the West Indian camp, ending the day at 219 for five. Knott fell for 87 after a 163-run partnership, but Greig went on. He scored his hundred, shepherded the tail efficiently, and was ninth out —to Julien, giving him his fifth scalp — for 148. England managed to reach 395.

Rowe walks in

Rowe walked in with the usually destructive Roy Fredericks towards the end of the second day. From the very onset, it seemed like he was in the ‘mood’, caressing the ball softly as possible, and watching them beat the hapless fielders to the boundary. He outscored Fredericks easily — something few batsmen have achieved in Fredericks’ career. West Indies finished the day at 83 without loss, with Fredericks on 24, and Rowe exactly twice that.

Despite his otherwise stylish approach, Rowe had unleashed the stroke early in his innings that has achieved an iconic status in the history of the game. In Gideon Haigh’s words, “Early in his innings against England at Kensington Oval, Bridgetown, Barbados, in March 1974, he received a bouncer from Bob Willis. He smashed it flat into the stand at square-leg; it travelled most of the way at head height.”

The English began well the next morning, but Rowe set off right from the very beginning. Fredericks was reduced to a mere spectator as he rushed past his fifty, and when Fredericks was finally bowled by Greig for 32, West Indies had scored 126, and Rowe was eyeing his hundred. It was then that Alvin Kallicharran walked out to join Rowe.

It was a treat for the audience. Both were elegant batsmen. While Kallicharran’s strength lay in his classical technique, remarkable footwork, and textbook strokes, Rowe was graceful in a different manner altogether: he drove well, even on the rise or off the back-foot. His back-foot cover drive, his signature stroke, was something people would walk to watch. He played the late-cut too late for anyone’s comfort. He stepped out against spinner, often to great results. And suddenly, he hooked one so hard that it struck the opposition like a bolt of lightning.

Rowe and Kallicharran kept making merry at the expense of the English bowlers. They matched each other stroke for stroke, and carried on past the lunch and tea intervals. Rowe had already reached his hundred, and Kallicharran followed him there within no time. By the time Greig found his way past Kallicharran’s defense, the little man had scored a 191-ball 119 with 18 strokes to the fence. The two had added 249 runs in 251 minutes in an exhilarating display of batting. It was also a new second-wicket record partnership for West Indies against England, going past the 228 set by Bob Nunes and George Headley.

Rowe was not going anywhere, though. He raced to 200 — the second one in his career, and his first since his debut Test. He lost Clive Lloyd, again to Greig, and Vanburn Holder kept him company at stumps on day three. Rowe was on 202, and West Indies were 394 for three, a single run behind England.

The crowd poured in by the thousands on the fourth day, eager to watch Rowe reach new milestones. As Tony Cozier said, “The whole of Barbados, it seemed, was there to see him bat... gates were broken, walls were scaled, and even high-tension electric cables were used as a means to enter. Rowe himself and other players had to be escorted through the mass to enter the ground through a fence.”

Rowe did not disappoint them. Greig picked up his fourth wicket — that of Julien — early in the day, but not before Rowe went past his own highest score. As Kanhai and Sobers both fell early, it seemed that West Indies would fold early, and Rowe would not have the time to make it big.

But then, out walked Deryck Murray. The gutsy Trinidadian warded off the penetrating English bowlers, while Rowe carried on. Soon afterwards, he went past Headley’s 270 not out – the highest score by a West Indian or England, and also the highest score by a Jamaican.

He soon reached the coveted 300-mark, and the crowd went erupted. They had interrupted play twice – when Rowe had reached 100 and 200, but this time they did not disrupt play. It was the first triple-hundred scored in Sabina Park, and is possibly the most aesthetically pleasing of all Test 300s in the history of the sport.

When Rowe finally fell for 302, hitting Greig to Geoff Arnold, he had scored 302 in 436 balls with 36 fours and that famous six. The entire crowd rose in a standing ovation, cheering him all the way off the field. At the end of the innings, Rowe had reached 955 runs in 10 Tests at an average of 73.46.

The aftermath

Kanhai declared at 596 for eight, securing a 201-run lead and allowing Murray to reach a well-deserved fifty. Greig bowled 46 overs spread over close to two full days, picking up 6 for 164. In the process, he became the first Englishman to score a hundred and take a five-for in the same Test.

England began disastrously, with the fast bowlers — Vanburn Holder, Andy Roberts, and Garry Sobers — all striking early, leaving England reeling at 40 for four. Once again Greig joined Fletcher, and the duo took the score to 72 for four at stumps.

Greig failed for the first time in the Test when he fell to Lance Gibbs for 25 early on the final day. It seemed over at 106 for five, but then, Knott walked out, and he played another rearguard innings — getting involved in a dogged partnership, this time with Fletcher. The fact that Gibbs could not bowl long spells due to an injury did not help, and the English batsmen steadily clung to their tasks.

Fletcher and Knott took England past the innings-defeat mark, and the Test seemed to be poised for a draw as Fletcher reached the three-figure mark. However, Kanhai resorted to use the medium-pace of Lloyd. When the Test seemed to be over, Lloyd broke through, trapping Knott leg-before, and bowling through Chris Old’s defense the very next ball. However, Arnold managed to play out 36 balls, Fletcher remained not out on 129, and England managed to salvage a draw.

In 2004, Rowe’s 302 was voted the best innings by a Jamaican, ahead of Headley’s 223 and 107.

Brief scores:

England 395 (Tony Greig 148, Alan Knott 87; Bernard Julien 5 for 57) and 277 for 7 (Keith Fletcher 129, Alan Knott 67) drew with West Indies 596 for 8 declared (Lawrence Rowe 302, Alvin Kallicharran 119, Deryck Murray 53 not out; Tony Greig 6 for 164).

(Abhishek Mukherjee is a cricket historian and Senior Cricket Writer at CricketCountry. He generally looks upon life as a journey involving two components – cricket and literature – though not as disjoint elements. A passionate follower of the history of the sport with an insatiable appetite for trivia and anecdotes, he has also a steady love affair with the incredible assortment of numbers that cricket has to offer. He also thinks he can bowl decent leg-breaks in street cricket, and blogs at http://ovshake.blogspot.in. He can be followed on Facebook at http://www.facebook.com/ovshake and on Twitter at http://www.twitter.com/ovshake42)

- Login to post comments

Recent comments

9 years 11 weeks ago

9 years 31 weeks ago

9 years 35 weeks ago

9 years 38 weeks ago

9 years 39 weeks ago

12 years 6 weeks ago

12 years 20 weeks ago

12 years 40 weeks ago